- Home

- Justin Lloyd

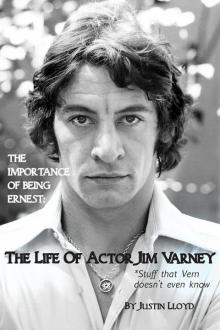

The Importance of Being Ernest Page 6

The Importance of Being Ernest Read online

Page 6

An ad agency named McDonald, Carden, Cherry and Ferrell was holding auditions for several female actors for a commercial for Purity Dairies. In the spot, a drill sergeant named Sergeant Glory demonstrated how to open the new plastic milk jug that Purity was now using. The character addressed two needs of the client: advertising the product and educating the customer about its new packaging.

As the camera pulled back, it was revealed that Sergeant Glory was not speaking to soldiers but to a group of female shoppers. (According to Thom Ferrell, Melissa was attempting to land one of the female roles.) Thom Ferrell remembers his first encounter with Jim:

“Melissa said she was with someone I should take a look at. He had been doing theater in Lexington and wanted to work in Nashville. I saw his face and thought it was interesting. At first I didn’t consider him for the part of Sergeant Glory, but he impressed me on how he could change characters in a second. I gave him some of the Sergeant Glory lines, and he was great. I spent more time with him explaining that I had made arrangements with the Marines for some mannerism training, and the hair and the earring would obviously have to go. The best I remember is that he snapped to attention, saluted and replied, ‘Yes, sir!’”

The first Sergeant Glory commercial was a success, and soon the character was using his Army clout in subsequent commercials to motivate everyone from dairy workers to actual cows into producing a superior product.

Just as Jim’s famous Ernest character would years later, Sergeant Glory inserted humor into a product where few saw advertising potential. Years later when being interviewed, Jim talked about the character and how the dairy industry had never before had a wow factor when it came to marketing. He jokingly claimed, “In the dairy business you either like milk or you don’t. There’s no superior cow.” Organic farmers these days would probably beg to differ.

In addition to Sergeant Glory, Jim began performing in other TV ads for the agency using characters from his vast arsenal. Jim played everything from a Hungarian ringmaster to a sleazy car salesman who smoked a cigar and wore a pencil-thin mustache. It was the car-salesman commercials where John Cherry first experimented with filming Jim using a wide-angle lens. The way in which it amplified Jim’s facial features worked well for the tone Cherry wanted. The wide-angle lens would become the standard when Ernest came along.

Taking advantage of Jim’s ability to imitate famous people, Cherry also used Jim in radio ads imitating such celebrities as John Wayne.

During the time Jim was working with Cherry, he remained vigilant in his quest to make it on Broadway. He decided to return to New York in the summer of 1973. Watkins was still living there, and Jim hoped that he could help him find new opportunities. Just to have a good friend close by made the big city less lonely. According to Liles, Watkins was “quite the moral support” for Jim for many years.

Jim’s dreams were big, but his bank account was not. Jim lived in a rundown apartment in Spanish Harlem. He was a starving artist. Liles came to see Jim in September 1973. Liles was living in Boston and doing well, working in PR, as well as training salesmen for a casket company. When Liles saw Jim’s apartment and the malnourishment beginning to show on his frame, he took Jim out to buy groceries. As Liles remembers, “Jim was grabbing up boxes of oatmeal, bags of potatoes, jars of peanut butter, and it just went on.”

The following Saturday Liles met up with Jim at Watkins’ apartment. The three decided that Jim should try out some of his stand-up material at a popular new comedy club in the city: Rick Newman’s Catch A Rising Star. It was open-mic night. During the cab ride over, they threw out lines and bits for Jim to consider. After they arrived, Jim was able to grab one the last spots. Even though his material was far from polished, Jim received a warm reception. That was enough for him to want to return. With the encouragement of other rising young comics like Freddie Prinze, Jim’s performances grew stronger. He also performed at another comedy club in the city called Pip’s. It looked like stand-up was a better gateway for advancing his career than Broadway.

Still, he wanted to act, so much so that Jim returned to Lexington to save up more money and work on new routines for an eventual stab at Los Angeles. He thought maybe television or movies might hold opportunities. After seeing comedian Jimmie Walker land a starring role on the TV hit “Good Times” and watching Prinze rise to fame on “Chico and the Man,” Jim hoped that playing the big clubs in Los Angeles would bring him similar success. The area had become the place to be for aspiring comedians thanks to Johnny Carson relocating “The Tonight Show” to Burbank.

But soon after his return to Lexington, a new romance began to take precedence over his career. Jim moved into an apartment with a new girlfriend and started to retreat from entertaining and, to his family’s dismay, life altogether. Coincidentally, Liles had also moved back to Lexington after leaving his job in Boston. Liles lived close by and stopped by to see Jim several times a week. They would talk about acting and kick around ideas for routines and characters. It was obvious to Liles that both Jim and his girlfriend were not good for each other. He remembers seeing plates full of cigarette butts and decaying food piled up around their bed.

Jim’s family didn’t see much of him during this time. Sister Jake remembers going to his apartment once after he had asked her for money. When she arrived, Jim met her out front (likely, Jake surmised, so she wouldn’t see the inside of his place). Jim’s father did little to intervene. He figured Jim’s struggles would help him realize acting was no longer in the cards, and he would soon begin working toward a real profession. But Liles knew Jim had real talent, and he wasn’t cut out for a regular job. Liles believed all Jim was lacking was confidence and motivation.

Liles’ efforts to motivate Jim finally paid off one day when Jim asked him to be his manager. Liles, surprised, replied, “What does a manager do?” Jim paused and then said, “I don’t know … manage?” Liles figured that whatever a manager did, Jim needed one. Liles believed then, as he does today, that Jim was in desperate need of moral support. Jim trusted Liles as someone who had his best interests at heart and would not take advantage of him financially. Liles looked at Jim’s career from a long-term perspective: He believed Jim had broad appeal – that he could play numerous roles, not just country characters. Meanwhile, Jim’s family approved of Liles for many reasons including the fact that Liles never used drugs or drank to excess.

Over the next few months Liles let Jim come over to his apartment any time he wanted to call long-distance to Nashville. Liles, as well as Jim’s family, hoped that if Jim could get something going he would leave his girlfriend behind. It wasn’t long before Betty Clark found work for Jim, and he was heading to Nashville in his father’s car. After a short stint recording radio ads, Jim returned to Lexington excited about how things had gone. Liles encouraged him to return to Nashville and agreed to join him and work on new material if Jim would commit himself to working hard. Jim agreed. He and his girlfriend eventually parted, and Jim began concentrating full-time on his career again. Jim moved to Nashville first in the early fall of 1974, and Liles followed six weeks later. The two found a place to share in the basement of Dottie’s Massage Parlor on Eighth Avenue. Along with managing Jim, Liles also paid his living expenses for about two years. Liles recalls Clark saying, “Thank God he has someone to help him.”

In no time Clark got both of them small roles playing Confederate soldiers in Johnny Cash’s “Ridin’ the Rails: The American Railroad Story.” Liles actually had no acting ambitions of his own and took the role because Clark asked him to. The one-hour TV special followed Cash as he took viewers back to important moments in the history of the American railroad. Cash narrated and sang railroad-themed songs throughout the production.

The filming of Jim and Liles’ scene took place at the House of Cash – Johnny Cash’s recording studio, which also housed his publishing operation in Hendersonville, Tenn. In the scene, the two sit at a nighttime campfire in the company of fellow Confederate sold

iers while Cash sings “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” At one point, the camera pans across the faces of the soldiers, pausing on Jim who stares off into the distance. The grim look on Jim’s face seemed to echo Cash’s subsequent line about how the starving soldiers were barely alive in the last days of the Civil War. Jim could probably relate after his time in New York.

During the taping of “Rails,” Jim ran into his friend Jack Routh; the two had met years earlier. Routh was a singer-songwriter and husband of Carlene Carter, the singer and daughter of June Carter, who was by now Cash’s wife. Routh was also friends with Loney Hutchins, who ran the House of Cash publishing operations. Jim and Liles became good friends with Routh, Hutchins and their wives.

In the late spring of 1975, Liles convinced Jim to go to a local club called the Exit/In for a showcase night and perform stand-up. Despite his success in New York, Jim was nervous. He confessed to Liles that he had bombed in Nashville once before, when he was in town for Sergeant Glory work. Jim had been staying at a motor inn where an outlaw country singer was performing. Jim and the singer were talking during a break, and Jim asked if he could go onstage and perform a few minutes of material. The crowd’s response was not what he expected: not a single laugh or chuckle in the house. Liles worked to build Jim’s confidence back up while helping him prepare new material. Liles even went so far as to promise Jim he would join him onstage to perform if Jim bombed again. Liles was glad he didn’t have to go through with his promise. Jim became an immediate hit, enabling Liles to get him additional bookings.

From the beginning, Jim’s stand-up act was built upon his strength of imitation. One of Jim’s early influences was comedian Jonathan Winters, who also used family members and local people from his hometown of Springfield, Ohio, as the foundation of many characters. Two of Winters’ most popular characters were Maude Frickert and Elwood P. Suggins. Maude Frickert was based on an aunt of Winters’ who, despite being crippled and bedridden much of her life, had a funny way of expressing herself. Winters would wear a dress, no make-up, glasses and a wig with a bun when portraying Frickert. He described her as a “hip old lady” whose age and conservative appearance allowed him to talk about controversial subjects without offending his audience.

Elwood P. Suggins was a hillbilly; Winters said he was based on men who had come from Kentucky to work in the Springfield factories. In one popular routine called “The American Farmer,” Winters portrayed Suggins as a farmer who was paid by the government not to plant crops. Although the money was good, Suggins struggled to define for people what he actually did as a farmer.

Jim took his similar gift of mimicry and turned it into hilarious depictions of colorful characters also based on people in and around his hometown. Jim’s innate ability to imitate Southerners made his material all the more authentic and funny. Although his parents did not have strong Southern accents (a Kentucky accent is more Midwestern as compared to, say, West Virginia), they did use colloquial phrases, many of which were uniquely Southern. Jim grew up hearing his mother say “over yonder” and the always-colorful, “She doesn’t know s––– from apple butter!”

Jim used various small towns in Kentucky and Tennessee as backdrops for his stories. Some of the most memorable were fictitious places such as the notorious Bulljack, Ky. Like Winters, Jim gave his characters peculiar names such as Clyde Spurlin and Bunny Jeanette. Bunny was a female beautician who competes in talent contests demonstrating her skill rolling hair with frozen orange-juice cans. Clyde was a confused old man who calls a welding company inquiring about how they might repair the steel plate in the back of his wife’s head. There was even a dubious county coroner named George Asher who embalmed the living.

Of all of Jim’s early characters, mountain man Loyd Roe is arguably the funniest. In Jim’s act, Loyd often talked about his 8-year-old son named Mistake. He claimed the child weighed 250 pounds and was over six feet tall. Mistake didn’t have toys like normal kids. During one routine, Loyd talked about the chainsaw that Mistake carried around in a shoulder holster.

Some of the characters Jim brought to life in these routines would eventually resurface in various incarnations in the many movies, commercials and TV shows in which Jim would star. Loyd became Ernest’s uncle, “Lloyd Worrell,” in the television special “Hey Vern, It’s My Family Album.” The character later made his uncredited big-screen debut as the snake handler in the movie “Ernest Saves Christmas.”

Soon after Liles joined Jim in Nashville, he browsed the yellow pages in the phone book for talent agencies and found out that William Morris had recently opened an office in the city. Before he got a chance to follow up, a William Morris representative approached Liles after one of Jim’s performances at The Exit/In. The rep had heard about Jim from the club’s owner and was interested in signing him. Jim was skeptical at first, but Liles assured him the man was legitimate.

After some discussion, Jim eventually signed with William Morris. The signing had no effect on the business relationship between Jim and Liles, who remained Jim’s manager. The first thing the agency needed was a bio of Jim. Liles quickly wrote up a page and a half of information. Liles admits, “The ‘spin’ and the BS was a little heavy but it worked.” Also attached to the bio was a list of Jim’s talents:

Accents and Dialects

Arabic

Australian

Carpathian

Italian

Irish

Mexican

Puerto Rican

Russian

Turkish

Welsh

Scotch – Edinburgh, Glasgow

British – Cockney, Earls Court, Liverpool, Midlands, Yorkshire

Impressions

Richard Burton

Peter O’Toole

Humphrey Bogart

Paul Lynde

John Wayne

Special Skills

Buckdancing

Hamboning

Eefing (an Appalachian type of vocal percussion similar to beatboxing)

Juggling

Knife throwing

Acrobatics

Fencing

Dulcimer

Coin-Dexterity Tricks

Tightrope Walking

Speed Bag

Eye Crossing – independent control of eyes

After signing with William Morris, Jim and Liles had the expectation of bookings on the college circuit and exposure to TV, commercial and film departments in New York and Los Angeles. A videotape of Jim’s commercials was made and copies distributed throughout the agency. Unfortunately, they didn’t generate any interest at the New York office. They found the humor too “rural” and couldn’t see past the production values to Jim’s acting. Still, he got more bookings in Nashville, and although he didn’t know it yet, the signing would pay off when he eventually reached Los Angeles.

Nashville wasn’t Los Angeles, but it still had a number of big stars, perhaps none bigger than the “Man in Black” himself, Johnny Cash. He showed up one evening at the Exit/In with his daughter Roseanne to see singer Dan Fogelberg. Jim happened to be the opening act that night. Liles remembers a line of people extending down the side of the building to the street waiting to get in. Liles spotted Cash and his daughter, and decided to introduce himself as a friend of Cash’s son-in-law Jack Routh. “I invited him to come into the club as our guest. He declined because he was uncomfortable cutting in front of so many people.” Liles didn’t give up, explaining that his offer was more of a favor to a friend’s father-in-law than a gesture to a famous star. Amused, Cash agreed to follow him in. Liles’ invitation paid off. As he recalls, “Cash was knocked out by Jim’s act and told Jack (Routh) and Loney (Hutchins) how great he thought he was.” (Although Jim and Liles had played extras in Cash’s TV special about the American railroad, they had not gotten to know him personally.)

Routh and Hutchins continued to stay in touch with Liles and Jim. They had also seen one of Jim’s performances at the Exit/In and were impressed. Ev

en though Routh and Hutchins had nothing in common professionally with Jim and Liles, the four had mutual respect and a desire to see each other succeed. Around this time Routh had a single released that was produced by Chet Atkins. Jim and Liles would constantly call the radio stations and request it.

Jim continued his stand-up appearances at the Exit/In, including a particularly well-received act when opening for Dr. Hook (a country-flavored rock band also known as “Dr. Hook & the Medicine Show”). Liles remembers the impact it made at the time:

“When Jim opened for Dr. Hook and the Medicine Show, that was a big deal. They had been opening for the Rolling Stones on a long European tour, and Dr. Hook got the audience so worked up, that the Stones had no place left to take them. So … Dr. Hook took over the ‘headlining’ position, and the Stones started going on first. That was an amazing achievement for any band in 1975. Jim had gone over great that night. His confidence, timing, everything was spot-on. The audience had Bobby Bare, Jessi Colter, Shel Silverstein and a bunch of people from the real Nashville musician scene. John (Johnny Cash) had heard about that.”

Routh and Hutchins updated Cash about Jim whenever they could. It wasn’t long before they arranged to bring Cash to see Jim perform again at the Exit/In. This time didn’t go as smoothly as before. In fact, it really didn’t “go” at all. Jim was supposed to open for outlaw country music singer David Allan Coe, but it turned out that the singer’s contract had a rider specifying no opening act. Jim couldn’t perform. (He had never received a confirmation from William Morris that would have given him the information.) But Jim ended up giving an impromptu performance to Cash, Coe and a few of their friends outside the club at the end of the night. Liles remembers:

“After Coe’s show, Cash, Loney, Jack, Coe and Jim were in the parking lot for a long time talking, laughing and cutting up. Jim was on. He was ripping off quips, one-liners and making jokes in character voices. Johnny was cracking up, as was Coe. Coe had on this outrageous outfit that looked like three cowboys and an Indian rolled into one. … parts of the vest looked like someone had sprayed it with silver paint. He had feathers in his big, oversized hat and was generally like a mid-’70s peacock. After a while, when everything was flowing smoothly, Jim sort of slapped Coe on the arm and said, “You know, I got an outfit just like that. Did you get yours at Sears too?” It was a sort of an Ernest voice. It cracked up Coe, and Cash liked it also.”

The Importance of Being Ernest

The Importance of Being Ernest